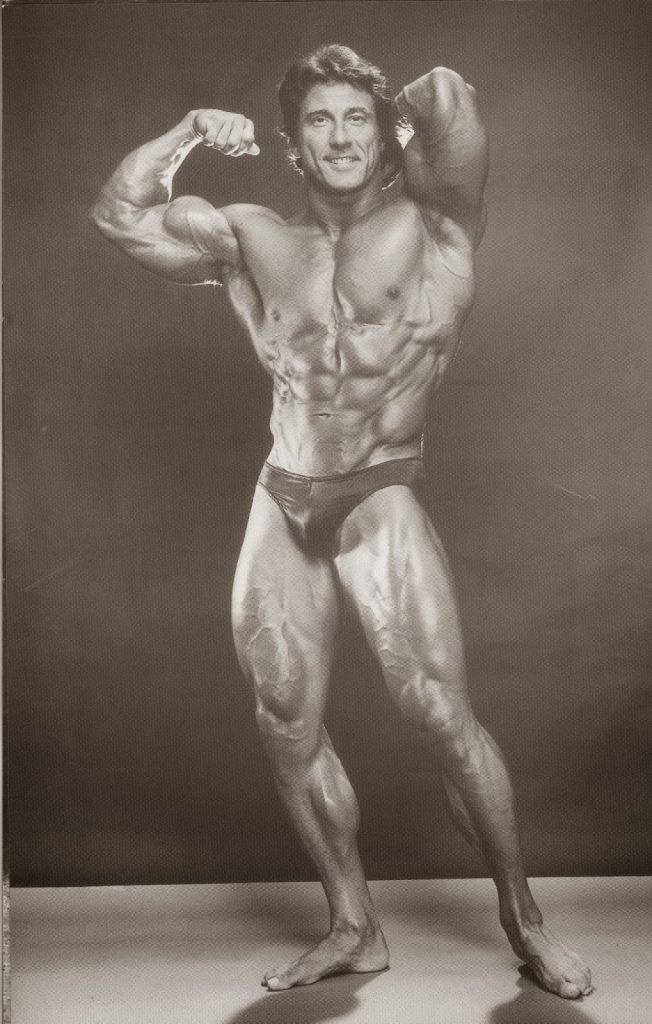

For a few years, you’ll have the classical, Zane-like physiques winning top bodybuilding shows, and everyone in every gym in America will be training with isolation exercises, completing high-rep sets, and trying to “pump” their way to a symmetrical physique. Then, a few years later when most people have tired of the swimmer look, powerful physiques will return to the forefront of magazine covers and bodybuilding stages. Soon, you’ll have every kid in America squatting, benching, and dead lifting their way through 3-rep sets in attempts to be the biggest guy in the gym. Though the pendulum swings every few years, it appears we are certainly currently entrenched in a “power” phase, where the bigger man is considered better, and the better man wins, of course.

Professional bodybuilders used to train using the compound movements to attain a certain level of muscle mass, then “cruise” much of the time they were a pro, attempting to hold the size they had, but more importantly focusing upon finishing movements to refine the mass they already had to emphasize their strongest attributes. However, as the weight of the athletes onstage has increased over the last decade (mostly due to changes in sports pharmacology) many bodybuilders have found it imperative to keep training for power, even after winning the pro card with what used to be considered adequate size.

The result of this power phase is that many of the top physiques in the world have a near-identical look to them. You have the top guys using the same power exercises, following the same diets and drug regimens, and ending up looking the same when they take the stage. Those finishing movements, which bring out the spectacular unique aspects of bodybuilders, are being bypassed, as the guys complete the same mass-building exercises to keep up in this size game. Also, injuries are more rampant than ever before. Despite the improvements in surgical technology, 2 or 3 Top Ten bodybuilders seem to incur a career-threatening injury each year as a result of a torn lat, pectoral, biceps, or triceps, muscle groups which do tend to be vulnerable to heavy training after 10 or 15 years of continual mass training.

Given time, the trend will swing the other way. Bodybuilding fans will tire of seeing the same identical monsters onstage, and marketing efforts (and therefore trophies and covers) will return to the smaller yet more symmetrical arms of the “pump” bodybuilders. All we can do in the meantime is realizing that no one bodybuilding physique is most pleasing to all groups, as bodybuilders come in every shape and size.